By Dr Alan Smith, Specialist in Public Health Medicine, the National Screening Service

The NSS has had a few questions recently asking what do we mean when we talk about ‘the limitations of screening’. This blog is aimed at building an understanding of some of the facts about screening, including why we know that when we offer a screening programme, with all its known benefits, we do this knowing that it will not work for everyone.

Just as it’s not possible for everyone to benefit from surgery or a new drug, not everyone will benefit from screening. We all have increased expectations of what can be achieved in the 21st century but unfortunately medicine is not perfect and never will be and there are limits to what it can achieve for each of us. Screening programmes are no different. There are limits to what a screening programme can achieve.

What does screening set out to do?

Cancer screening is the process of identifying those people amongst an apparently healthy population who may have an increased chance of cancer. By ‘apparently healthy population’ we mean that they do not have symptoms or any other concerns that they might be unwell.

The purpose and indeed the main benefit of screening is to detect cancer at an early or what we call a pre-cancerous stage and to reduce the number of new cases and deaths associated with the cancer. Other benefits may be the use of less aggressive treatments because it can start at an earlier stage of the cancer’s development and lead to an improved quality of life

All of this sounds great……BUT…..medicine is not perfect.

Why screening does not work for everyone

Most people who have cancer will have an abnormal screening result – this is called a true positive and most people without cancer will receive a normal result – this is called a true negative. These are often called the benefits of screening. All good so far but notice that we said MOST people.

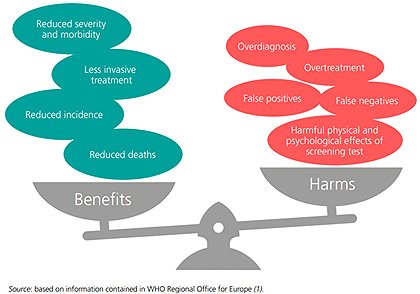

Some people with cancer will receive a normal or negative screening test result – this is called a false negative and some people without cancer will receive an abnormal or positive test result – this is called a false positive. These are often referred to as the harms of screening.

With a strong focus on quality, screening programmes can reduce false negative and false positive results but unfortunately cannot eliminate them.

All screening programmes then have a difficult balancing act. Balancing the known benefits with the known harms. See Figure 1 below. And just as we don’t like to think of the possibility of unsuccessful surgery or that the new medication won’t work, we tend not to think too much about the harms of screening or that it will not find my cancer. That is normal. That is human nature.

It is probably fair to say that the ‘false negatives’ are the most discussed and reported on type of harm. And it is true that it can be the most upsetting for the person affected. Put simply: they did everything right, but the programme ‘missed’ their cancer. Unfortunately, this cruel ‘why me’, ‘what if’, ‘if only’ realisation, sometimes with life changing consequences, is and will always remain an integral part of all population screening programmes.

Figure 1 - The benefits and harms of screening

Why we still bother with screening programmes

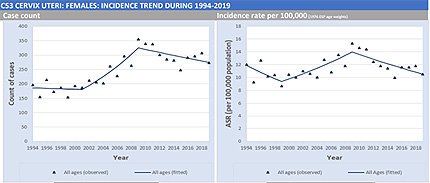

Screening programmes that are up and running because they have been proven to benefit most of the population, despite the known harms. In the case of cervical cancer, for example, we can see very clearly that the introduction of population cancer screening in 2008 has led to a reduction in the number of new cases. See Figure 2. The graph continues downwards. Many thousands of lives have and will be saved by cervical cancer screening.

Figure 2 - Incidence rate in cervical cancer since 2008

The bar for setting up a screening programme is high. The evidence must be clear that most of the population will benefit from the screening programme and that the harms can be as few as possible. The case for setting up a population screening programme is scrutinised in detail and is typically done using an agreed set of international criteria (known as the Wilson & Jungner principles) to guide policymakers in deciding whether to introduce a new screening programme in their country.

So, the population benefits but some individuals will be harmed?

Yes. It is a reality that not every individual within a screened population can benefit from participation in a population screening programme. Some will be harmed. For example, despite the impressive graph in Figure 2 above, cervical screening will not prevent all cases. Overall, it is widely accepted that cervical cancer screening will fail to prevent between 30-35% of cancers - even in well run programmes.

Why? Medicine is unfortunately not perfect.